One-fifth of Earth’s ocean floor is now mapped

Image copyright: NIPPON FOUNDATION-GEBCO SEABED 2030 PROJECT

Image copyright: NIPPON FOUNDATION-GEBCO SEABED 2030 PROJECTWe’ve just become a little less ignorant about Planet Earth.

The initiative that seeks to galvanise the creation of a full map of the ocean floor says one-fifth of this task has now been completed.

When the Nippon Foundation-GEBCO Seabed 2030 Project was launched in 2017, only 6% of the global ocean bottom had been surveyed to what might be called modern standards.

That number now stands at 19%, up from 15% in just the last year.

Some 14.5 million sq km of new bathymetric (depth) data was included in the GEBCO grid in 2019 – an area equivalent to almost twice that of Australia.

It does, however, still leave a great swathe of the planet in need of mapping to an acceptable degree.

“Today we stand at the 19% level. That means we’ve got another 81% of the oceans still to survey, still to map. That’s an area about twice the size of Mars that we have to capture in the next decade,” project director Jamie McMichael-Phillips told BBC News.

Image copyright: FUGRO

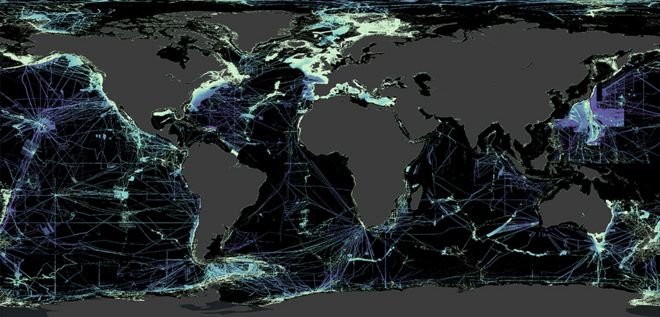

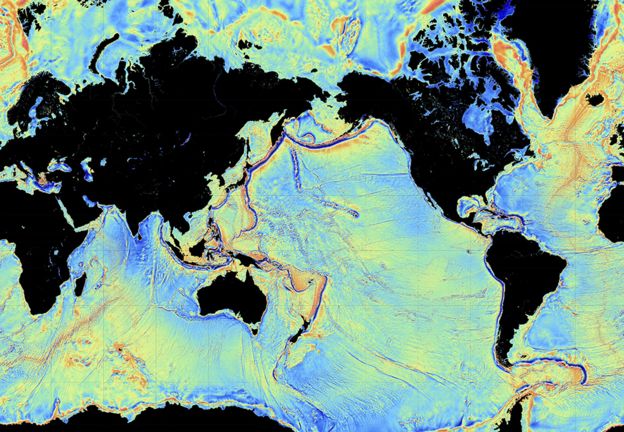

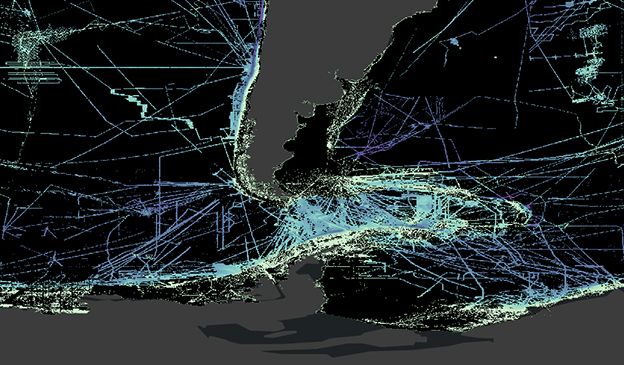

The map at the top of this page illustrates the challenge faced by GEBCO in the coming years.

Black represents those areas where we have yet to get direct echosounding measurements of the shape of the ocean floor. Blues correspond to water depth (deeper is purple, shallower is lighter blue).

It’s not true to say we have no idea of what’s in the black zones; satellites have actually taught us a great deal. Certain spacecraft carry altimeter instruments that can infer seafloor topography from the way its gravity sculpts the water surface above – but this only gives a best resolution at over a kilometre, and Seabed 2030 has a desire for a resolution of at least 100m everywhere.

Image copyright: D.SANDWELL ET AL/SCRIPPS

Image copyright: D.SANDWELL ET AL/SCRIPPS

Better seafloor maps are needed for a host of reasons.

They are essential for navigation, of course, and for laying underwater cables and pipelines.

They are also important for fisheries management and conservation, because it is around the underwater mountains that wildlife tends to congregate. Each seamount is a biodiversity hotspot.

In addition, the rugged seafloor influences the behaviour of ocean currents and the vertical mixing of water.

This is information required to improve the models that forecast future climate change – because it is the oceans that play a critical role in moving heat around the planet. And if you want to understand precisely how sea-levels will rise in different parts of the world, good ocean-floor maps are a must.

Much of the data that’s been imported into the GEBCO grid recently has been in existence for some time but was “sitting on a shelf” out of the public domain. The companies, institutions and governments that were holding this information have now handed it over – and there is probably a lot more of this hidden resource still to be released.

But new acquisitions will also be required. Some of these will come from a great crowdsourcing effort – from ships, big and small, routinely operating their echo-sounding equipment as they transit the globe. Even small vessels – fishing boats and yachts – can play their part by attaching data-loggers to their sonar and navigation equipment.

One very effective strategy is evidenced by the British Antarctic Survey (BAS), which operates in the more remote parts of the globe – and that is simply to mix up the routes taken by ships.

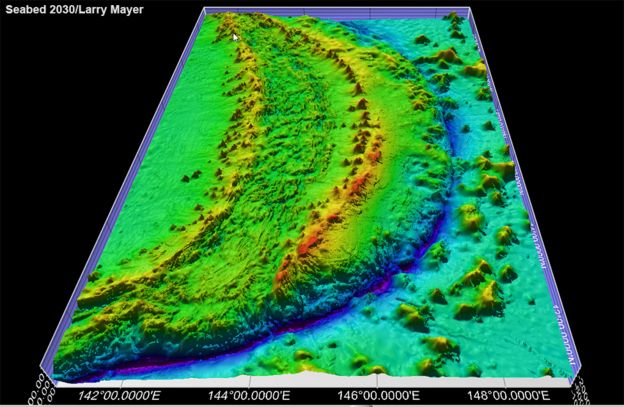

“Very early on we adopted the ethos that data should be collected on passage – on the way to where we were going, not just at the site of interest,” explained BAS scientist Dr Rob Larter.

“A beautiful example of this is the recent bathymetric map of the Drake Passage area (between South America and Antarctica). A lot of that was acquired by different research projects as they fanned out and moved back and forth to the places they were going.”

Image copyright: OCEAN INFINITY

Image copyright: OCEAN INFINITYNew technology will be absolutely central to the GEBCO quest.

Ocean Infinity, a prominent UK-US company that conducts seafloor surveys, is currently building a fleet of robotic surface vessels through a subsidiary it calls Armada. This start-up’s MD, Dan Hook, says low-cost, uncrewed vehicles may be the only way to close some of the gaps in the more out-of-the-way locations in the 2030 grid.

He told BBC News: “When you look at the the mapping of the seabed in areas closer to shore, you see the business case very quickly. Whether it’s for wind farms or cable-laying – there are lots of people that want to know what’s down there. But when it’s those very remote areas of the planet, the case then is really only a scientific one.”

Jamie McMichael-Phillips is confident his project’s target can be met if everyone pulls together.

“I am confident, but to do it we will need partnerships. We need governments, we need industry, we need academics, we need philanthropists, and we need citizen scientists. We need all these individuals to come together if we’re to deliver an ocean map that is absolutely fundamental and essential to humankind.”

GEBCO stands for General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans. It is the only intergovernmental organisation with a mandate to map the entire ocean floor. The latest status of its Seabed 2030 project was announced to coincide with World Hydrography Day.

Image copyright: NIPPON FOUNDATION-GEBCO SEABED 2030 PROJECT

Image caption: Drake Passage is the stretch of water between South America and Antarctica

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk

Source: https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-53119686#